It begins with the mewling baby in the pram, unloved irritant for the teenage mother posing with cigarette at the roadside, desperate for attention from the hoodied boys.

Then comes the toddler, naked from the waist down and dribbling as it crawls over the remains of a carpet, unseen by a parent staring vacantly at a giant widescreen television.

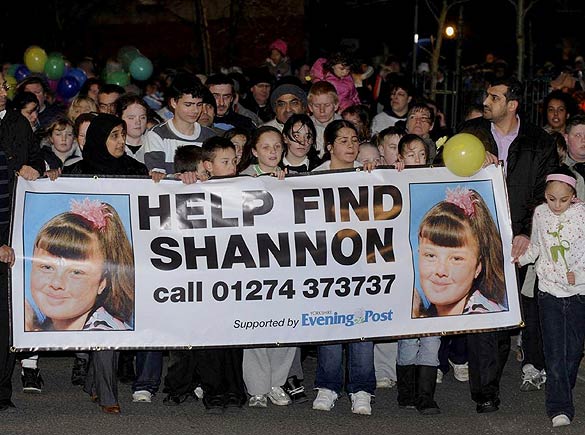

Next comes the primary school pupil. Perhaps Shannon Matthews, bonny-faced but pumped so full of pills for 20 months that you can almost hear her young frame rattling on the way to school.

She did not come home on February 19, because her debt-ridden mother – hoping to earn a reward for her safe return – arranged to have her kidnapped by her boyfriend’s inadequate uncle.

But for that fateful act, no spotlight would have fallen on the streets of ugly 1930s red-brick semis clinging to a hillside on the western edge of Dewsbury, West Yorkshire.

Shannon, unnoticed, unloved, would have become a young teenager, an age when some of her peers will begin to follow in the footsteps of Michael Donovan, the girl’s kidnapper, towards a series of petty juvenile convictions.

For others, childhood dreams will fade to grey reality. Sooner or later, fleeting relationship will be followed by pregnancy, single parenthood and a plunge into a benefits culture designed to reward fecklessness.

It is a path well trodden. On such estates, the badge of economic and emotional deprivation passes seamlessly from one generation to the next.

Of course, there are the survivors who do not bow to the seemingly inevitable – those fortunate or strong enough to find work, to build a secure family unit. They are the ones who try to forge a sense of community spirit, the ones living in the homes whose fenced gardens are not dumping grounds for household waste. But they are the exceptions.

Between 1981 and 2006 the proportion of social housing tenants of working age in full-time jobs fell from 67 per cent to 34 per cent.

A Centre for Social Justice report, published this week, might have been talking about Dewsbury Moor when it presented a stark assessment of the decline of working-class social estates during the past 50 years.

It spoke of a “cycle of destructive behaviour”, of a housing system that has “ghettoised poverty, creating broken estates where worklessness, dependency, family breakdown and addiction are endemic”.

Another report, from the charity Barnardo’s, showed – perhaps unsurprisingly – that the children most prey to criminal and antisocial behaviour, inadequate education, poor health and substance misuse were those from the poorest communities.

Martin Narey, the Barnardo’s chief executive, was speculating about the future of Baby P, had the boy lived, when he spoke of childhood deprivation creating a teenage “parasite . . . helping to infest our streets”. He could have been talking about the likely fate of Karen Matthews’s children.

The 33-year-old had seven children by five men. She had been living for three years with Craig Meehan, 22, who thought – wrongly, a DNA test would later establish – that he was the father of the youngest.

In September, Meehan was sentenced to 20 weeks in prison after being convicted on 11 counts of possessing child pornography. The offences came to light when his computer was seized by police during the search for Shannon.

The other significant adult in Shannon’s story was Donovan, Meehan’s uncle, a man described by his own barrister during the kidnap trial as “a pathetic inadequate . . . a loner, dysfunctional, strange, an oddball”.

The youngest of nine children, he was bullied at his special school and told the jury at Leeds Crown Court that he had “all sorts of difficulties trying to understand things in life”.

He was obsessed with cars but needed more than 100 lessons to pass his driving test before finding work as a delivery driver.

His boss sent him out one day to put £20 of diesel in his pickup, then watched later in bemusement as Donovan repeatedly drove back and forth past the firm’s premises. When he eventually returned he explained that he had been able to fit only £18.48 into the tank, so he kept driving around until he could return to the petrol station and squeeze in the remaining £1.52.

The defence tried to cast the 40-year-old as an unworldly innocent who took Shannon because her mother had threatened to kill him. This was the man selected by Matthews to care for her daughter. On February 19, as she walked home after a school swimming trip, Donovan bundled her into his car.

For the next 24 days, as West Yorkshire Police launched their biggest investigation since the 1970s hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper, he held her drugged and tethered in his flat, one mile from Dewsbury Moor.

We may never know what happened to Shannon during that period. The child was so heavily doped that she has never been able to give a coherent account of her ordeal.

By contrast, all of Britain knew what her mother was doing. She was crying for the television cameras, pleading for the safe return of her little angel.

Behind closed doors the distraught public face was replaced by the giggles of a woman who, according to her friends, behaved as though she did not have a care in the world.

So was she mad, bad or irredeemably stupid? What is clear is that she “lied, lied and lied again” to police, offering at least five explanations for her role in Shannon’s disappearance.

Though Matthews received £400 a week in benefits, she was deeply in debt to the doorstep loan sharks who prey on impoverished communities such as Dewsbury Moor.

It may have been a reward plot from the outset, but it also seems possible that she initially arranged for Donovan to take Shannon for a few days because she intended to leave Meehan and planned to go to the flat a short while later with her other children.

That scenario sees her losing her nerve at the last moment, being too scared to tell Meehan, then sitting back and letting events take their course, realising at an early stage that a newspaper’s £50,000 reward for Shannon’s safe return would solve a lot of financial problems.

Whatever the motivation, it is clear that the welfare of Shannon played no role in her calculations. This was, after all, a woman whose daughter had been systematically doped with sedatives, antidepressants and painkillers for at least 20 months, presumably with the aim of rendering her passive and thus less of a nuisance.

As the police built a picture of the extended Matthews and Meehan families, plus those of Matthews’s former boyfriends and the various fathers of her children, they found themselves with a logistical nightmare. There were soon several hundred names, including one murderer, many with criminal convictions and a number of convicted sex offenders.

Curiously, no one close to the family thought to mention the existence of the man who was holding Shannon.

Pity the children brought into such a world. Two sheets of paper, not shown to the jury, offer a glimpse inside a little girl’s troubled mind.

On one, screwed up in a bin at Donovan’s flat, was a child’s drawing of an explicit sexual scene between two adults. Mummy and Mick, was Shannon’s accompanying caption.

The other was a note found in her bedroom at her mother’s house. On it was a verbal exchange between the girl and her sibling.

“Do you think we’ll get any tea tonight?” asks one child.

“We may get a packet of crisps if we keep quiet,” comes the reply. “Don’t say anything, though, ’cos we’ll be beaten.”

After her rescue, Shannon was asked by child psychologists whether she wanted to go home. The reply came immediately. No.